Historian in Residence - World War II: Cockshutts with Wings

Shelly McElroy is the 2022 Historian in Residence

British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain stepped off his British Airways flight and declared to his relieved audience that there was to be, “Peace for our time.” It was September 1938 and Chamberlain had just penned a deal with Germany that was seen as a political breakthrough; it was hoped that the agreement, which divided up Czechoslovakia, would ensure a peaceable future. In Canada, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King assured Canadians, “Your sons will not be sent into any foreign wars.” The Prime Minister was requesting advice on running the country from his mother … who unfortunately had been dead since 1917.

Whatever the politicians were saying or not saying, it was becoming apparent to the average Canadian that the second dreaded war with Germany was unavoidable. Imagine that you are a western Canadian reading about the latest Calgary Broncs game (the precursor to the Calgary Stampeders) in the Calgary Herald. Marching alongside the sports scores are towering black headlines that read, “HITLER REMAINS POPULAR DESPITE BROKEN ELECTION PROMISES.” With hindsight, the impact is chilling, and surely no one reading the continued threats emanating from Germany at the time would have felt easy in their minds.

"Royal Visit by King George and Queen Elizabeth to Calgary, Alberta.", 1939-05-26, (CU1215664) by Calgary Photo Supply Company. Courtesy of Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

In May of 1939, King George and Queen Elizabeth made a cross country tour of Canada. The royal couple were welcomed by joyful crowds, but it was clear that this was a business trip that was looking for support from the Canadian people and their government. Just a few weeks after the couple left Calgary, in September of 1939, Canada declared war on Germany.

Canadian life transformed instantly, with the focus of every industry imaginable converting to supporting the war effort. For the foreseeable future, the emphasis would be on the production of food, and fighting. The fact that any pre-1940s tractors exist at all is somewhat of a miracle, considering the war effort’s appetite for scrap metal. It was Canada’s role to feed Britain, supplying grain and meat. Since food production was supposed to increase at the very time that Canadian farmer labourers were joining the army, that meant that there was suddenly a keen interest in machines that could compensate for the labour shortage: self propelled combines, balers, and binders.

That had an impact on some very familiar tractor manufacturers. We’re going to tell you about that story today.

"Advertising photograph for Cockshutt Plow Company Limited, Calgary area, Alberta.", [ca. 1950], (CU1217900) by Burkell, Lorne. Courtesy of Libraries and Cultural Resources Digital Collections, University of Calgary.

Cockshutt was a small Canadian manufacturer, and their pull-type combines had less capacity than the self propelled combines that Massey Harris had been tinkering with for the last twenty years. Cockshutt was passed over when Massey Harris received a large ration of steel to continue manufacturing their product, and Cockshutt farm equipment production was reduced to a quarter of their pre-war levels. With the company in a vulnerable position, the way for them to stay afloat was to join the war effort.

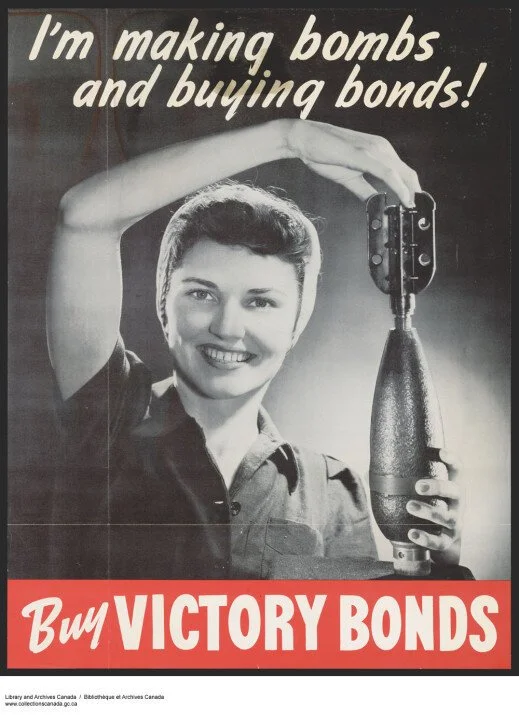

At first, the federal government was wary of the idea that companies that were used to working with cast iron would have the expertise to adapt to munitions work, but they were to be proven wrong. And with so many men in the army, it was a legion of women, the Cockshutt girls dressed in their white coveralls, who were going to be taking on the lion’s share of the work.

“At the Brantford plant, women were employed almost exclusively,” writes Wm. H. Cockshutt in the book About Cockshutt. Women were building parts for planes, including undercarriages for Avro Anson bombers. The Avro was quickly outdated as later bomber designs were faster, but they became a trainer plane – and Canada was expected to deliver them.

At first, it was thought that only piano manufacturers would have the expertise to bend plywood into the intricate shapes needed to form the Avro’s shell and wings, but as Cockshutt’s labour force grew to nearly six thousand, they demonstrated that this was an ability they could perfect.

Mosquito fighters were needed, too. Cockshutt debuted high temperature exhaust rings, landing gear, manifolds, and pilot seats for the bomber, which became one of the most versatile aircraft used during the war. Many of those parts came from Cockshutt factories. Women at the Cockshutt Frost & Wood plant also processed hand grenades; they were finished and sent to an arsenal to be filled with explosives. Women were building aircraft, and their husbands, brothers, sons, and friends were flying them. Families separated by the war bonded over those five little words, “Mom, thanks for the bomber!”

WWII Poster. Library and Archives Canada.

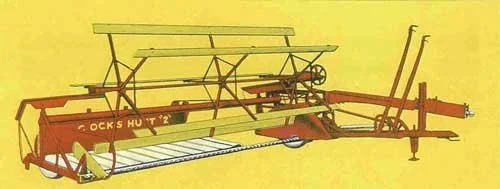

Cockshutt also debuted their No.2 Swather during the war. This was a product intended for their western Canadian market, as many eastern farmers would not have been acquainted with the problem of having to cut huge expanses of grain that had ripened at different rates. Cutting a crop just before it reached peak maturity and leaving it to dry was a concept that made sense to western Canadians. The sturdy, lightweight No.2 was extremely popular; for fifteen years it captured some 60% of the western Canadian market.

Cockshutt No. 2 Swather. Image from the International Cockshutt Club.

So, what became of the planes after peace returned in the summer of 1945?

In the article “Warbird Relic Hunters of the Wild West,” Richard de Boer explains that the Hurricanes, Avros, Mosquitos and other aircraft that had defended Canada during the war were being sold and that many farmers were interested in acquiring them for spare parts that they could adapt to be used in other machinery.

In 1946, Ian Willdig’s father was a seventeen year old who had missed out on participating in the war effort. But when an Avro Anson came on the market, Gordon decided that he wanted to own one. Ian believes that Gordon would have loved to fly with the RCAF but was told that his place was on the farm. As Gordon was born in 1927, he was also a bit young for the war, which was over by the time he would have been old enough to join. Gordon never got his pilot’s licence or flew the aircraft, to the relief of family members, however it was a cherished artifact.

Ian shares that he once found a photograph online of the training airfield in Ontario where his dad’s Anson Avro had flown. Ian then did a double take and realized that the photograph also pictured the plane his father purchased! In the photograph, the eventual Willdig Anson is the one in the middle, FP-953. Gordon’s Anson was put into service on 24 August 1942 and flew 2021 hours and 15 minutes before it was retired on 12 November 1946. The Willdig family still have the original bill of sale, showing that Gordon paid $200.00 for the plane. The family lore is that the wings had to be cut off so it would fit on the truck transporting it to the Willdig’s farm at Keoma, Alberta.

Training airfield in Ontario where his Gordon Willdig’s Anson Avro had flown.

As you now know, WWII aircraft were constructed of things like wood and fabric, which meant that they were extremely vulnerable to the elements. A parted out Avro could literally dissolve in a back pasture. Richard de Boer and his friend Jon Spinks made it an obsession to travel across western Canada salvaging what they could. Richard met with the Willdig family early in the 1980s when an Avro Anson that is now on display in The Hangar Flight Museum was being restored.

The Willdig Anson Avro made several “organ donations” to the Avro that is currently on display in Calgary. Ian and Richard de Boer both note that George Ryning was key to the restoration; George was a well-respected flight instructor at SAIT. When Gordon Willdig learned about the Avro restoration project, he was passionate about what George was doing and it was a source of pride for him to be able to contribute; among other things, the rudder of Gordon’s plane was saved and put on the Anson in Calgary. We would like to thank Lauren Maillet of The Hangar for contributing the photographs of the restored Avro Anson on display to this article.

Restored Avro Anson on display at the Hangar Flight Museum. Lauren Maillet.

Restored Avro Anson on display at the Hangar Flight Museum. Lauren Maillet.

Although George was proud of being able to share parts from his Avro with the restoration project, he and his family kept some things as well. Gordon died in 2014; recently the lovingly restored propeller from Avro FP 953 was completed and put on display … in Ian’s living room. “I wanted the memory to live on. Respect, honour, have the artifact front and centre, not in storage,” Ian tells us. Ian’s friend Ron Poffrenroth mounted it on a beautiful display that magically draws the eye, so it goes right to the propeller. Justin Willdig, Gordon’s now seventeen year old grandson, helped on the restoration project too. Justin is the same age his grandfather was when he originally acquired the Anson all the way back in 1946.

And that is a story about Cockshutts with Wings, and about the connection the Canadian tractor manufacturer had with a global war effort and with a local farming family.

The lovingly restored propeller from Avro FP 953 on display.

Propeller detail.

Cockshutt Aircraft Divsion.

Read More:

Cockshutt: The Complete Story | Compiled by the International Cockshutt Club Inc.

About Cockshutt by Wm. H. Cockshutt

A Brief History of Cockshutt Aircraft Division: Cockshutt Quarterly, Winter 2017

Warbird Relic Hunters of the Wild West by Richard de Boer: https://www.vintagewings.ca/stories/warbird-relic-hunters

Shelly McElroy is the curator of Pioneer Acres Museum in Irricana, Alberta. Pioneer Acres Museum is one of the largest agricultural and industrial history museums in Alberta with a collection of thousands of artifacts. Shelly has a background in education, agriculture, counselling, and museums. Her primary field is the natural grass pasture behind the museum where she works that is full of crocuses, meadowlarks, and the occasional unwelcome skunk.

The Historian in Residence is presented in partnership with Calgary Public Library.